Teaching Artificial Intelligence in K-12 education through educational robotics and remote learning: the role of students and the mobilization of the school community

“ Studying is not an act of consuming ideas, but of creating and recreating them. ” (Paulo Freire)

- The motivation to teach Artificial Intelligence in K-12 Education

As it is an increasingly pervasive technology that has expanded its field of action in a short period of time, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been applied in actions ranging from the area of Marketing, Medicine, Engineering, Politics, in services related to Human and Financial Resources and even in leisure activities, including Games and Social Networks. We find smart devices in countless technological resources and our youngsters are users of most of them.

The ubiquitous nature of this technology has caused people to interact with AI passively without considering, for example, that this interaction exposes their individuality and privacy. This fact is enhanced by the facilities that its use provides. Many people are not careful about its use and are not careful with the permission to obtain their personal data.

One of the ways to raise awareness and clarify the population about this technology is via Literacy in Artificial Intelligence actions, so that users interact with devices equipped with this resource in a critical and less passive way. The best place for these actions to take place is in K-12 education.

There are important reasons why the school should include subjects related to AI teaching in its curriculum. Among them, we can point out the impacts that AI has caused on human relations in 21st century society (Druga, 2018). In addition, the expansion of the integration of this technology in day-to-day resources points to changes in the professional world, enhanced by the fourth industrial revolution[1].

In this sense, the update of the National Curriculum Guidelines for Secondary Education in Brazil, a document dated November 21, 2018[2], proposes for the Formative Itinerary[3] of the Mathematics and its Technologies area that curricular arrangements be structured allowing, among other topics, studies on AI:

“deepening of structuring knowledge for the application of different mathematical concepts in social and work contexts, structuring curricular arrangements that allow studies in problem solving, (…), robotics, automation, artificial intelligence, (…), considering the context and the possibilities of provision by education systems”

According to Libâneo (2004), the school can no longer be an institution isolated in itself and separated from the surrounding reality but integrated into a community that interacts with the broad social life. In fact, the school environment is a space with the potential for this topic to be addressed and the AI’s operating logic can be presented and discussed as a means of clarifying to students what makes smart devices so invasive. Initiatives like this provide the training of new generations of citizens aware of the benefits, risks, and care related to the use of such devices.

- The implementation of AI teaching at the Polo Educacional Sesc

In order to relate Mathematics, Computer Science and New Technologies to the high school curriculum, in 2019 I proposed a course for the Mathematical Formative Itinerary, called Math Maker.

The course is a mathematics teaching-learning proposal inspired by the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) approach and integrates robotics, automation, programming and AI in the teaching of the subject.

Just as the Brazilian Ministry of Education proposed actions to modernize and update teaching through the Common National Base Curriculum[4], the STEM approach is a government initiative that emerged in the United States with the aim of improving the learning of exact sciences.

In November 2009, former US President Barack Obama presented the “Educate to Innovate” initiative as a collaborative effort between the federal government, the private sector and the nonprofit and research communities. Thus, STEM education was recognized as an approach that brings greater relevance to the teaching of concepts in mathematics, physics, chemistry and computer science topics.

This approach provides the student with a leading role in their learning and develops important skills for the 21st century professional. This professional will find a labour market that will demand a new set of cognitive skills and abilities, previously only accessible to specialists, promoting the democratization of various tasks.

At the Polo Educacional Sesc, one of the activities that comes from the actions that the Math Maker course promotes is the Artificial Intelligence Club.

- The first year of the Artificial Intelligence Club – 2019: The construction of the Frankie robotic device and the realization of face-to-face workshops

In the first year of the Club, students participated in workshops that promoted the introduction of machine learning concepts[5] via educational robotics. During 4 months, it carried out activities related to pattern recognition, database definition, training, classification and accuracy using the Python programming language[6].

As an AI resource, the WiSARD Weightless Neural Network was used, an acronym that highlights the names of the creators (Wikie, Stonham and Aleksandre’s Recognition Device). WiSARD is considered a model of simple understanding because the operations that it performs are mostly of binary logic. To understand how it works, it is necessary to know how to perform basic mathematical operations, among them, perform percentage calculations and recognize representations of binary images. In addition, the student need to have skills that involve combinatorial thinking and random processes. Anyway, subjects that are easy to understand for high school students, and for this reason, it was chosen as an AI library for these actions.

In the institution’s Maker Space[7], the Frankie robot (Pictures 1), was prototyped (F.R.A.N.K.I.E stands for Fostering Reasoning and Nurturing Knowledge through Informatics in Education). This robot makes it possible to teach students the mechanisms behind an artificial neural network, promoting the learning of what makes an AI resource so important in countless applications.

Pictures 1 – Robot Frankie prototyping stage

It is important to highlight that the use of robotics to promote the teaching of concepts of Mathematics and Computer Science enables a multidisciplinary experience and creates different forms of interaction with the learning space.

During the workshops, the students “taught” the robot geometric shapes that, when recognizing them, should make a decision in the environment (Pictures 2). Through a database of images created by them, students trained the algorithm to recognize the geometrical figure and later move in a predetermined direction. Upon realizing that Frankie’s AI algorithm sometimes did not properly recognize the image learned and consequently moved in a different direction than expected, students compared it to an autonomous car and raised the following question: “Whose responsibility would it be if an AI, driving an autonomous car, makes an inappropriate decision and causes an accident? The owner of the car or those who developed the AI algorithm?”.

Pictures 2 – Conducting field activities with the Frankie Robot

In addition to the engagement of students in the workshops that promoted the teaching of AI resources with robotics, the first year of the AI Club showed that the theme goes beyond the learning of mathematics and computer science concepts. The meetings with the students pointed to the need for a multidisciplinary discussion.

At the final meeting with workshop participants, some questions were raised, among them the power that AI has in processing a large amount of data and transforming it into privileged information. One of the participants said that he had read that the data is the new oil, referring to the phrase said by Brittany Kaiser, former director of the extinguished British company Cambridge Analytica, and which corroborates a statement by computer scientist Kai-fu Lee, which in one of his books says that “if artificial intelligence is the new electricity, big data is the oil that powers generators”.

In addition, students show concern for ethics on the part of those who develop AI algorithms and those who obtain and use the personal data of the population through these algorithms. They also pointed out fears about the social impacts of using this technology such as the automation of numerous fields of work and consequent unemployment. Young people assessed that unqualified citizens would find it difficult to allocate themselves professionally and reflected that investment in Social Programs would be essential for a reality with widely implemented AI.

Through these questions, we can see that the results of the 2019 workshops exceeded the limits of technology learning and provided an important reflection on ethical and social issues regarding AI.

- The second year of the Artificial Intelligence Club – 2020: The set of remote actions involving experiments and debates

With the pandemic in 2020, the Club maintained its activities with remote experiments and organized biweekly Lives (Livestreaming) to debate some issues regarding AI. For the actions of the second year of the Club, I counted on the partnership of the researcher and co-worker Isaac D`Césares[8]. It is important to emphasize that for entrepreneurial educational actions to work with quality, establishing partnerships with other educators is essential.

Machine learning experiments were introduced using free web interaction platforms such as Teachable Machine[9] and QuickDraw[10] and converged to hands-on programming activities on the Google Colab platform[11], which allowed students to collaboratively program machine learning libraries on the web in Python language.

Online workshops were promoted using AI resources such as Linear Regression Algorithm, Scikit-Learn Clustering, Decision Tree Algorithm and Neural Networks. One of the workshops, organized by members of the Club (Pictures 3), provided experimentation with WiSARD.

Pictures 3 – Online workshop promoted by students

On the other hand, the debates promoted by the organization of the AI Club, into Live format, were attended by educators from the Polo Educacional Sesc and professionals from various fields of knowledge, among them former students of the institution, as well as important researchers like Professor Paulo Blikstein from Columbia University.

Two debates can be highlighted, in which students discussed the ethical, social and political issues in relation to the use of AI in the management of the personal data of the population by public and private organizations, whose themes were: “Artificial Intelligence and Ethical Implications” and “Power and Politics in the Digital Age” (Pictures 4).

Pictures 4 – “Artificial Intelligence and Ethical Implications” Live & “Power and Politics in the Digital Age” Live

In the Live “Artificial Intelligence and Ethical Implications” (http://bit.ly/ia_ethical), values and principles involving the implementation and use of AI by technology companies were discussed. A student described the case of an American company called Target, reported in the book “The Power of Habit”, with the title “How Target knows what you want before you know it”, highlighting how companies use their customers’ personal data to recommend targeted products and boost their sales.

Menstruation Apps were also highlighted as an example. In them, the user can note, in addition to the date of her period, emotions and symptoms, if she had sexual intercourse and when. Thus, the app can predict her next menstruation or indicate the possibility of a pregnancy. When users approve the Terms of Use, they allow their data to be used by companies without being aware that it can be shared and sold to other companies. For example, if the user checks in the app that she has dry hair, she can receive ads for hair products. The center of the debate was ethics and personal data.

In the Live “Power and Politics in the Digital Age” (http://bit.ly/ia_politics), it was discussed, among other topics, how AI is used in the dissemination of Fake News and targeted political propaganda.

During the Live the young people detailed the emblematic case of how the extinguished British company Cambridge Analytica[12] managed, with permissions given by users in the terms for using quizzes on Facebook, to have access to all their likes and likes from their network of friends. So they used that data to influence elections in the United States.

The students pointed out that in an action with 270,000 users who participated in these quizzes, the company had access to the data of approximately 87 million people. Based on their interactions, the types of citizens’ personalities were drawn up to promote political advertisements aimed at these people, with content that caused the polarization of society and influenced the country’s political destiny.

In their presentation, the students pointed out a survey that revealed that analyzing 70 likes, Facebook “knew” the user better than a friend; with 150 likes, better than his parents; and to know the user better than his love partner, only 300 likes were needed. They emphasized the need to control access to this data so that what happened in the American election is not repeated in other elections.

The actions involving experiments and debates proved to be complementary, as the students dealt with the subject through the bias of those who had the most proximity to technology, those who had lived and experienced it. According to Paulo Freire, consuming ready-made ideas does not make an educator a scholar or a researcher, but participating in the process of creating ideas does. This process can be stimulated with actions in which the student assumes the role of protagonist of his learning via activities in which he participates in the construction.

Our next step is to expand the activities involving Artificial Intelligence`s resources in another project that will be called STEM + AI Club. The goal of this new approach is to ampliate the participation of the academic community in the discussions of the fourth industrial revolution and its impacts on our society.

- AI Club 2020 Remote Meetings

Meeting 1: Presentation: “Artificial Intelligence Club – 2020”

Meeting 2: Workshop: “Introduction to machine learning and the development environment”

Meeting 3: Debate: “Artificial Intelligence and Ethical Implications”

Meeting 4: Workshop: “Machine Learning Experimentation – WiSARD Weightless Neural Network on the Google Colab Platform”

Meeting 5: Debate: “Creativity and Artificial Intelligence”

Meeting 6: Workshop: “A Matemática por detrás de predição usando um Algoritmo de Regressão Linear”

Meeting 7: Debate: “Teacher training, Maker Movement and Artificial Intelligence in K-12 Education with Professor Paulo Blikstein – Columbia University – NY ”

Meeting 8: Workshop: “Clustering with Scikit-Learn: Working with Unsupervised Data”

Meeting 9: Thematic Panel at the Knowledge Festival of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro: “Artificial Intelligence in K-12 Education – The teaching of AI, and the teaching through AI. How can the school prepare for this new reality? ”

Meeting 10: Debate: “Power and Politics in the Digital Age”

Meeting 11: Workshop: “Classification using the Decision Tree Algorithm”

Meeting 12: Debate: “Artificial Intelligence contributions to human health”

Meeting 13: Debate: “Artificial Intelligence, Iot and Smart Cities: The contributions of Mathematics to a Society 5.0”

Druga, S. (2018) Growing up with AI – Cognimates: from coding to teaching machines. In: Dissertação (Mestrado). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Libâneo, J.C. (2004) Organização e Gestão da Escola: Teoria e Prática, 5. ed. Goiânia.

[1] Just as the first industrial revolution introduced machines into the production system, the second introduced electricity and the third introduced information technology, the fourth revolution encompasses a broad system of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics and the Internet of Things.

[2] https://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/51281622

[3] Formative Itineraries are curricular units offered by educational institutions that allow the student to deepen their knowledge and advance in their studies of interest or prepare for the working world.

[4] Document that defines the essential knowledge that all K-12 education students in Brazil have the right to learn.

[5] Machine Learning – is an AI field whose objective is to develop algorithms capable of improving its performance in specific tasks. Machine learning algorithms learn information directly from data without the need for a predetermined equation as a model.

[6] Programming language that can be used for the most diverse applications. It is Open Source and it was developed having as one of the main objectives to be easy to use.

[7] https://www.sesc.com.br/portal/noticias/educacao/espacos+makers

[8] https://www.linkedin.com/in/isaacdcesares/

[9] https://teachablemachine.withgoogle.com/

[10] https://quickdraw.withgoogle.com/?locale=en_US

[11] https://colab.research.google.com/

[12] The story can be seen in the documentary The Great Hack.

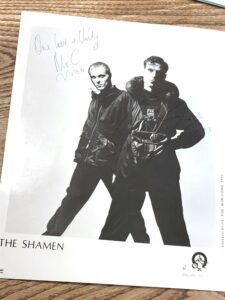

The Yamaha VSS-30

The Yamaha VSS-30 The Shamen – 1993

The Shamen – 1993 Daft Punk – Daftendirektour 1997

Daft Punk – Daftendirektour 1997 Erector set – 1930s Advertising

Erector set – 1930s Advertising 8-Bit Cross Stitch – Make Stuff North East Activity

8-Bit Cross Stitch – Make Stuff North East Activity